Beverley Bryan also spoke at the ceremony in which a Council building was given Olive Morris’s name. She now lives in Jamaica where she is Head of the Department of Educational Studies, University of the West Indies, Kingston.

Olive Morris

One of the founder members of the BWG (Black Women Group) was Olive Morris, who in her very short lifetime made an invaluable contribution to Brixton BGW, OWAAD (Organisation of Women of Asian and African Descent) and the Black communities in both Brixton and Manchester. Like Claudia Jones, she represents the kind of Black women who, over the years, have thrown themselves into the struggle in this country and made an indelible, if anonymous, mark.

Olive Morris’s short life was similar in most respects to the lives of the majority of West Indian women living in Britain today. She came to Britain at the age of eight to live with her parents, and went to a secondary modern in south London where she experienced all the inequalities and injustices of the British education system. She left at sixteen with no qualifications, but undeterred, she went on to college to study ‘O’ and ‘A’ levels while at the same time holding down a full-time job.

It was during this phase of her life, when she was only seventeen years old, that Olive carried out her first conscious political act, one which was to led her into organised political activity for the rest of her life. This was in 1969, when she went to the aid of someone who was being harassed in the street by the police. His crime was to have been driving an expensive car, which the police found suspicious enough to warrant an arrest. As a result of her intervention, Olive herself was arrested and taken to the local police station, where she was made to strip and was brutally assaulted. The incident did not intimidate her, however. It simply strengthened her opposition to racism and injustice.

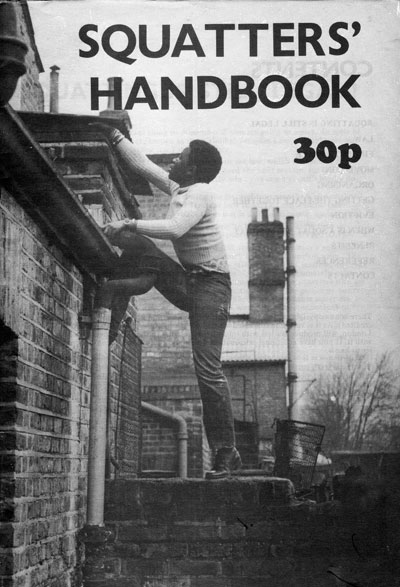

Olive went on to join the Black Panther movement, and it was here that she began to develop the political ideology which would determine her future actions. She gave a total commitment to the organisation’s work and development, and participated in nearly all of the battles which formed part of the community’s everyday life. She was in tune with the needs of the people, and always showed herself willing to take the initiative and act. This was certainly the case with the squatters movement in Brixton, when she organised with others like herself to squat because there was nowehere to live and no hope for a council flat. She became well known in the community for her willingness to help other Black people who were facing difficulties, whether with the schools, the police, housing, social security officials or the courts – whatever the issue, she was never too busy to offer support. For Olive, it was not just a case of doing things for those who couldn’t do it for themselves: it was her way of involving people in the struggle, showing by her own example the will to resist and to challenge.

After the decline of the Black Panther movement, Olive worked with some other Black women in the area ad with a group of brothers to set up Sarbarr Bookshop, the first Black self-help community bookshop in south London. During the same period, she helped form the Brixton Black Women’s Group, to which she made a lasting contribution. The political perspective she brought to the group helped it to develop a coherent political ideology, based on the needs of ordinary Black people in the community, which made clear links with other anti-imperialist struggles. She worked relentlessly to translate these ideas into practice, and most of her political work was done at grassroots level.

In 1975, she went to Manchester University to study for a social science degree. This in itself was an important step for Olive, who believed in education for the people. For her, going to university was not a status symbol, but an example to many young Black people of how to fight and win against a system which tries to push us to the bottom of the education pile and force us to compete against each other.

Unlike many students, Olive did not separate her work at the university from the struggles which were being waged in the rest of the community. In her work with the Manchester Black Women’s Co-operative and the Black Women’s Mutual Aid Group, which she helped to set up, she participated fully in the black community’s battles in Moss Side. Committed to furthering education rights for Black people, she campaigned with Black mothers for better schooling for their children and helped to set up a supplementary school and a Black bookshop in the area. Because she was an internationalist, she also worked at the university within the National Co-ordinating Committee of Overseas Students. She provided an essential link between international, community and women’s organisations, drawing the parallels between our experiences here and in the Third World.

In 1978, Olive visited China. The trip was of great significance to her, for she saw China as one of the countries which Third World peoples could learn a lot from, and which could serve as a model for us in self-help and self-reliance. The lessons she learn there were shared with everyone she worked with on her return. Sharing knowledge was always her practice.

Olive had always identified the relationships between the struggles of people in the Third World and those of the white working class. She recognised that it was a fight which had to be won through the contribution of both groups, and that we would need to work together if we were to bring about any meaningful changes. It was this awareness which was her greatest contribution to the political development of those she worked with.

When she returned to Brixton in 1978 after completing her studies, the work she had begun while in Manchester to launch OWAAD was taken up by other women in the Brixton Black Women’s Group. It was then that she began to suffer the symptoms of the cancer which killed her within the year. In her fight against leukemia, she displayed the same courage she has shown throughout her lifetime, and when she died on 12 July 1979, at the age of twenty-seven, she had already made her mark. She was mourned by all sections of the Black community, and by many others from outside it whose lives she had touched.

“Olive and I went to the same school. Even then she had that streak in her – in school, they would have called it rebelliousness or disruptiveness, but it was really a fearlessness about challenging injustice at whatever level. This made others very weary of her, she was so obviously a fighter. I saw her once confronting a policeman – it might have been when she was evicted. She went at him like a whirlwind and cussed him to heaven. And this policeman looked really taken aback, he didn’t know how to deal with someone who had no fear of him. He was meant to represent the big arm of the law. But because she was angry and she knew he was in the wrong, she didn’t hesitate.

She would take anybody on like that, even people in organisations if she thought that someone needed to expose their hypocrisy for mounting slogans and living a lie. Because of that, a lot of them saw her as a pain in the neck and she was too! She’d fight them physically, if it was necessary. If you moved with Olive, you couldn’t be a weak heart. She gave a lot of support to so many sisters though, when they came under pressure from the brothers at meeting or wherever. She was a real example, You didn’t see it then, of course, but that fearlessness of hers, and that genuine commitment she showed to the work she did made her stand out, made her special.

I remember when Olive was in Manchester, I went up to an education meeting she was organising with the Manchester Black Women’s group, and it struck me at the time how at home she was away from home. She had gone up to the university to study, but she made contact with people so easily that before you knew it she was right in there with the Black women in Moss Side, organising with them, taking things on. She could easily have found a student clique on the campus, but instead she sought out her people and just carried on the work we’d been doing in Brixton. But then she always was hot on personal commitment – not just showing willing, but showing determination. Her life is a kind of symbol to the people who knew her. People like Olive inspire you to resist.”

At her memorial ceremony in Brixton a few weeks after her death, several hundred people came to pay testimony to her remarkable courage and her fighting spirit. Those who knew her were left with her vision of a new society, and the lasting memory of one more Black woman who was not afraid to fight back.

Comments